Part 1 – Building the Dutch East Indies

Part 1 – Building the Dutch East Indies

In this trilogy Remco Vermeulen, Advisor Indonesia, searches for the shared past and shared future of the Netherlands and Indonesia. His personal journey of discovery leads from his own family history to today’s dynamic debate of cultural cooperation. Through this journey, his subjective and nostalgic image of Indonesia develops along with the complex and modern image in which many personal histories define the relationship between both countries.

My first image of Indonesia was shaped by the many stories my grandfather, or opi as we used to call him, told me as a little boy, and which he put in writing in the 1990s. His stories sketch an image of a carefree childhood in the Dutch East Indies.

Early childhood

In 1934 my opi’s brother builds a house in the village of Singosari, about 90 kilometres south of Surabaya, East Java. It is one of those typical Indo-European (or ‘Indo’) residences of the upper middle class, with all living quarters on the ground floor, shadowy verandas and high roofs with tiles and small openings for ventilation. My opi is about ten years old when he moves to Singosari with his parents, which is a small village amidst rice fields and tropical forests. After school he runs around with his dog and shoots pigeons with a small airgun. He has kite fights with the kampong children or helps his mother with baking Indo delicacies such as spekkoek, mocha cakes or koningskronen. In Surabaya, the big city, where he attends the Koningin Emma technical high school, he goes to the movies with his school friends who have Indo-Chinese, Dutch, Indo, Portuguese-Indo and Javanese backgrounds. Later, he goes to dancing evenings at the Indo Europees Verbond, at the Oranje Hotel or the Sociëteit with his older sister and brother-in-law.

Different memories

The memories of my opi have become my memories, like romantic scenes of an epic movie. Not long ago I reread his memoires. It still strikes me how multicultural he sketches the 1930s society of the Dutch East Indies. The light-heartedness he describes was of course partly due to his innocent, possibly naive, young perspective. But my opi was a man with a remarkably positive attitude. During the annual commemoration of the end of the Second World War in the Dutch East Indies on 15 August in The Hague, years ago, when one of the speakers held an emotional recitation of the traumatic experiences of his father in a Japanese internment camp, opi turned to me and whispered “it was not all that bad”. Had my opi, as an adventurous teenager, been lucky during his own internment? Or was this his way of comforting me or himself, as protection against the horrors so many had experienced in the Japanese internment camps or under heavy forced labour? I can no longer ask him these questions. But his memories, exceptionally detailed, remain. They stir my curiosity to the old and new Indonesia.

Stimulated by my work at DutchCulture I am increasingly realizing that the memories of my grandfather are only showing one side of Indonesia’s history. I know that many other personal stories and memories are by far not as beautiful as his. All those different stories and memories are becoming increasingly visible in the Netherlands and Indonesia, and they stimulate me to view my own family history in a new and broader context.

From trade to occupation

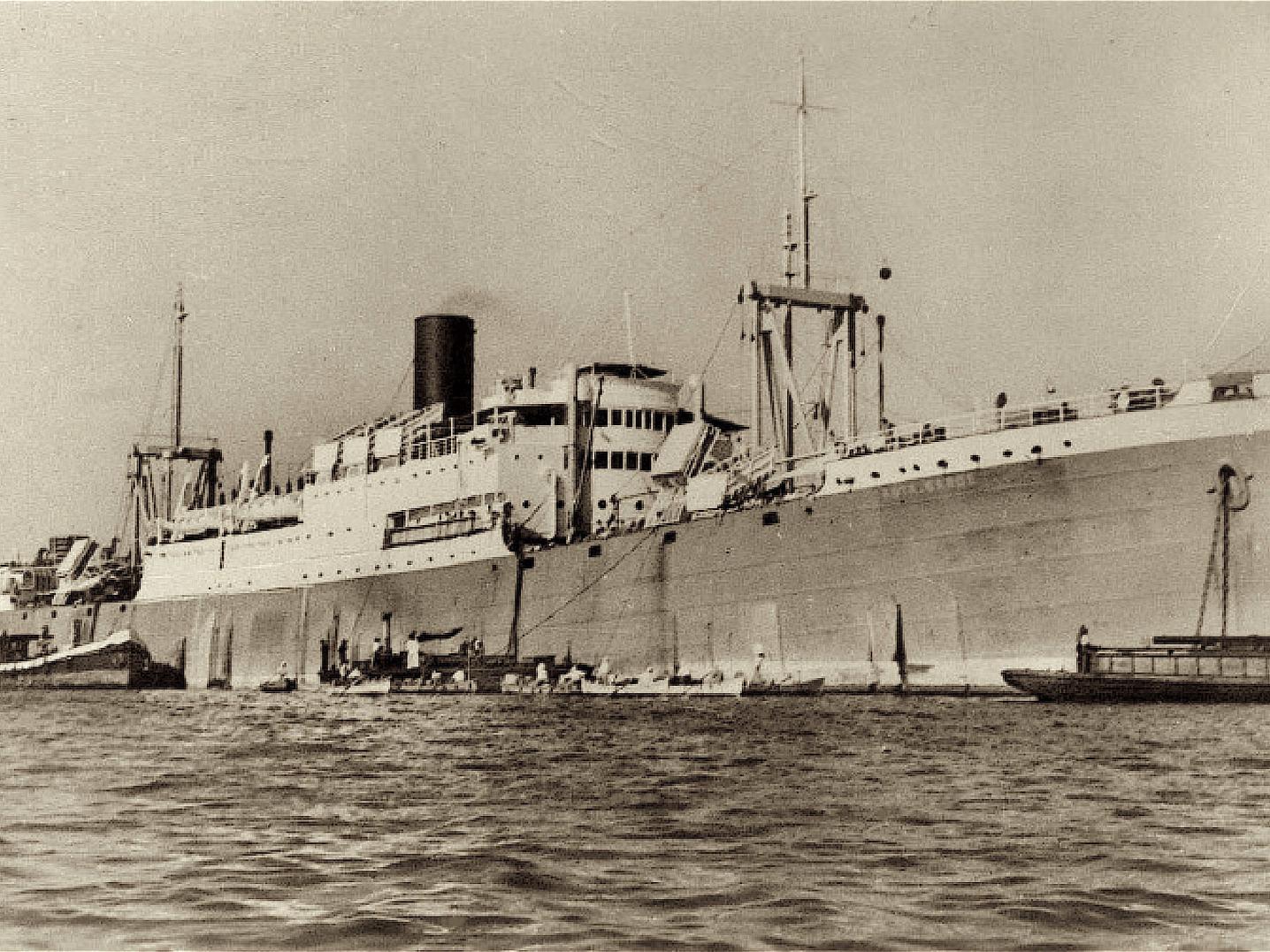

The multicultural society in the Dutch East Indies of my grandfather is partly caused by the Dutch colonial government, but has been part of the character of the archipelago since the dawn of time. In the Iron Age small islands are inhabited by different ethnical groups. The fertile volcanic soil offers a wealth of fauna and especially flora, of which the value is increasingly recognized: cinnamon, nutmeg, pepper and later on sugarcane, coffee, rubber, oil and so on. With boats the Chinese, the Arabs, the Portuguese and also the Dutch come to the archipelago to exploit the natural resources and to trade. The Dutch, led by the Dutch East India Company, settle permanently in the archipelago to protect their trade interests. Violence is not avoided here. On strategical locations fortresses and harbours are constructed. Batavia is the capital city.

Dutch and other Europeans are encouraged to settle in the colonies and beget ‘loyal’ offspring with local women. Only when the Dutch East India Company goes bankrupt in 1798 and all its property is appropriated by the state, the Dutch presence is expanded enormously at the expense of the sovereignty of local rulers and population. Initially the colonial government practices a so-called policy of abstention: the centralized government in Batavia is limited to Java and Ambon while on other, more remote islands cooperation agreements with local rulers are signed. In the second half of the nineteenth century the colonial government expands its power, by example of the British Empire, to the islands of Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes, Bali and Timor. Expansion is going hand in hand with bloody conflicts.

Cultural exchanges

Until then the archipelago is primarily a cash cow for the Dutch: natural resources are exploited on a large scale, shipped to the Netherlands for processing and sold for solid profits. Only in the late 1800s, under pressure of rising emancipation in Europe and out of an ‘ideal of civilization’, the colonial government reluctantly starts investing in society. Education (in Dutch!) and social facilities become accessible to (some parts of) society and regions get more self-determination. At the same time the Dutch living in the Dutch East Indies dress for special occasions in local dress of batik shirts, sarongs and kebajas. Meanwhile the famous ‘Indische rijsttafel’ becomes a status symbol of colonial hospitality equivalent to European banquets. Dutch and Indo architects integrate local architectural styles and elements with western Art Deco, Amsterdam School and Modernist styles into the New Indies Style.

Leaving the Dutch East Indies

Although the colonial government in Batavia primarily invests in Dutch - and to a lesser extent in Indo - citizenship, education and self-determination create more awareness and longing for independence among local communities. At the beginning of the twentieth century Indonesian nationalism is born. Representatives of this new movement try to enforce reforms with the colonial government. They only partly succeed, but when the colonial government is ousted after the invasion of Japan in 1942, there is no way back. After the surrender of Japan in 1945 the Indonesian nationalists take power. The Netherlands does not accept this and the Indonesian War of Independence is a fact. Eventually Indonesia gains its independence, and the Dutch acknowledge the new Republic of Indonesia in 1949.

At that time my opi does no longer live in his country of birth. He is one of the first to make use of the possibility to repatriate in 1947. Aged 22, he ventures to the Netherlands, a country where he had not been before but of which he speaks the language and has the nationality.

Read further Part 2 - Building Indonesia >

Read further Part 3 - Building a shared future >>